John G. Roberts III Electricians Mate on LST-325 Part 5: Homeward Bound

- msroberts0619

- Nov 21, 2024

- 12 min read

November 21, 2024

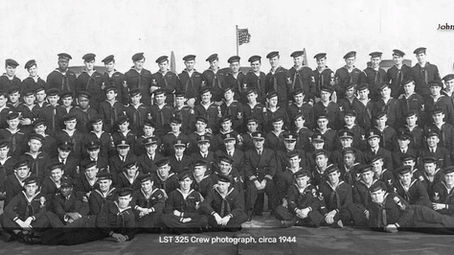

(Pictured above is the crew of the LST-325 taken in 1944 John is far right second row from top)

In our last posting LST-325 had made its final English Channel crossing following a supply delivery at Le Havre, France on April 10, 1945. They were of course stalked by German U-boats on their return but safely moored in the Portland Harbor. On April 12th they learned of the unexpected death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt from a cerebral brain hemorrhage. The entire crew mustered in dress uniforms on deck on April 14, 1945 to honor and observe 5 minutes of silence for FDR.

On April 17, the LST-325 fired up the engines and left Portland Harbor for the last time, cruising just a short distance to Plymouth Harbor where they were moored until the end of April. By that time, it is certain the entire crew had a mindful awareness that they had been working the resupply of Normandy and other ports in France for just one month short of an entire year. They accomplished that effort with no less than 44 trips back and forth across the English Channel. Such a gargantuan undertaking consisted of loading their ship to capacity, crossing the Channel, landing and unloading and finally recrossing the Channel to load more supplies. That daunting task was done essentially once each week for the entire period.

Now the crew of the LST-325 was just beginning the last phase of their wartime experience, finally preparing to leave the troubled waters for home, family and comfort. At this point, none of them could have even guessed that the long anticipated and relieving voyage back across the Atlantic would become one of the most horrifying of their entire time under fire.

On April 30, 1945 the crew and ship underwent a final material inspection by the commanding officer of LST Amphibious Craft of the 12th Fleet. They then moved from the pier and joined with a large number of LSTs anchored in the harbor also awaiting the journey back across the ocean to the United States. At 1215 hours on May 5, 1945 Captain Mosier ordered the engines fired up to get underway. “At 1350, the LST-325 passed through the Plymouth Harbor boom gates; the final time the ship would sail from an English port. Emotions were mixed among the crew, the excitement of returning to the United States tempered by the fact that some were leaving very dear friends behind.”

This was it! It was finally time for the crew to return home. They could only hope their journey would be safe and without incident or stray attack which they were apparently getting all too used to. Anyone who has ever been in the service for an extended period of time knows exactly what they were all feeling. They were just going about their business watching the days go by but underneath it all there is always a nagging concern. That feeling that now in the final hours prior to overwhelming relief and happiness some cruel twist of fate or other unexpected nonsense would unavoidably emerge right in their path to thwart their last efforts to reach peace and joy. After more than 2 years of experiencing almost everything the war could possibly throw at them nearly every single day, their concern would be forgivable. Perhaps their only solace to keep such concerns at bay would be their knowledge that they and their shipmates literally came through it all together, and still with life enough left to tell the tale. Confidence in being able to manage together through the inconceivable would undoubtedly help them through their final voyage.

Most of the crew began their time together in nearly wide-eyed innocence. But now they were proud, battle tested and assured, but also battle weary of the fight. Their hearts were filled with hope and expectations for their long return. All were most certainly reflecting upon their time together, knowing that they all survived because of the efforts of each of their buddies as a cohesive and confident crew working as a single dedicated unit. Such feelings were expressed by Don Martin, Motor Machinist Mate as he remembered, “I had been transferred off in Plymouth and saw the LST-325 leave and tears came to my eyes. I had gone through a lot with some great guys. They performed their jobs so I’m alive, and I performed my duty so they were alive.”

“The convoy made their final stop before heading across the Atlantic, entering the harbor at Belfast, Ireland on May 7. The next day they received the official announcement that all German forces in Europe had surrendered to the Allies. At last, the long war in Europe was officially over. That evening the fortunate members of the ships company that had liberty joyously joined in the wild victory celebrations in Belfast.”

The LST-325 was prepped and secured for open sea travel. Captain Mosier ordered the anchor hoisted at midnight, May 12, 1945. Now after more than 2 years and having admirably struggled through three of the most pivotal military invasions of the war, the crew of LST-325 were heading home. They were a part of Convoy ONS-50 and set their heading north-northwest to travel back across the temperamental north Atlantic.

Unfortunately, “Two days from Belfast, the convoy sailed into the fiercest storm the crew of the LST-325 had yet encountered. Monstrous waves, thirty to forty feet in height, pounded the convoy. Winds of near hurricane strength whipped the rain and blinding spray from the bow into driving needles that stung the skin. There was no chance of maintaining the convoy’s formation and soon the ships were scattered in the merciless storm. Time and again, the creaking and groaning ship would crest one monstrous wave only to slam head on into the next. Each time the ship went over a wave the screws would come out of the water and the engines would wildly race, and without constant vigilance on the throttles the engines would have shutdown because of the automatic over-speed cutoff.”

Back in 1945 there were no such things as seats and belts for everyone onboard. Every member of the crew had to find something to hang onto for dear life as they were furiously thrown about like rag dolls. “Shortly after midnight, the ship crested one more enormous wave and as her flat bottom slammed down into the wave’s trough a horrible shudder vibrated through the hull.”

It was John’s work area, the auxiliary engine room that called the bridge to sound the alarm that they were taking on a significant amount of water. It was flooding into the bilges from massive cracks in the forward bulkhead. Captain Mosier called for an immediate damage control report. Only a few moments passed before department crewmen began responding with their news. “The worst of it was that there was a four-inch crack in the main deck plates extending outward from the forward starboard corner of the cargo hatch. There were more cracks where welded seams between deck plates on the portside had separated and ruptured plates further forward where longitudinal support brackets to the cargo hatch had pushed through the deck. Several support brackets in the bulkheads from the tank deck all the way to the tanks and voids on the fourth deck forward of the auxiliary engine room. The ship was literally beginning to crack in two.” John Roberts’ recollection of it was, “We were in the North Sea in very rough weather when our ship started to crack in the area in front of the superstructure. The Captain was signaled that he could go back if he wanted to, but he said no. We laid in the swells sideways as our talented shipmates welded big patches over the cracking areas We got further behind the convoy.”

For an entire day crew shipfitters raced around looking for anything that would serve as a patch for the cracks throughout the core of the ship. Large metal plates were welded everywhere it could make a difference to bring the ship back to some kind of seaworthiness. The shipfitters even tore apart the tubing from the troop quarters to use as braces in various places all over the ship. “The Captain knew that if he kept the ship heading directly into the hammering waves that she could split in two, so he risked having her capsize by angling the ship sideways to the waves” as John had mentioned, while the welders performed their magic. Regardless of their herculean efforts, the ship still continued to take on water each time a large wave was hit. The bilge pumps had to be turned on every three hours just to try and keep up with the flooding.

Eventually late on the 15th the storm subsided and a calmness came over the sea easing the overwhelming fears of captain and crew. According to Gunners Mate Leo Horton, the captain had responded to a British vessel perhaps reaching out to assist LST-325 in a return trip to Belfast stating, “I got her over here and I intend to get her back.” And so, by some miracle the Atlantic was “as calm as a millpond” for the next several days when they finally approached New York on the 27th and were given orders to continue on to Norfolk, Virgina while the remainder of the convoy headed for moorings in New York.

“On may 31, as the Virginia coast was sighted off the starboard bow, Captain Mosier ordered the ‘homeward bound’ pennant hoisted on the main mast.” That characteristic and extremely long and narrow pennant appears to be almost a ribbon version of the US flag. The tradition associated with it is that it is flown on the main mast of a ship that has finally returned to the US after deployment overseas. It continues to be flown until sunset of the day of arrival and is then ceremoniously lowered and thereafter cut into small pieces to be given to each member of the crew. The LST-325 worked its way slowly passed the Cape Henry Lighthouse and up the James River as it headed to Hampton Roads near the US Norfolk Navy Base. At 0919 hours of May 31, 1945 the anchor chain was released and to the relief of all onboard, the LST-325 was finally, and safely home.

Eventually, LST-325 was docked at Norfolk and inspected for damage. Lieutenant Ted Duning remembered, “When we got to the dock in Norfolk an inspection was made of the hull and I heard a Lieutenant from the shipyard say we should never have made it across.” It was clear from the inspection that any repairs would be extensive and could not be done in Norfolk.

With no repairs planned in Norfolk, LST-325 was ordered to sail in a group of four other LSTs and head for New Orleans. John put it this way: “We went into Norfolk and thinking how great it would be to go ashore on arrival but we were not allowed to leave. We were told all we could do was send telegrams. From a list of messages many of them came out wrong. Then we went for six more days to New Orleans.” The grouping of ships left the next morning, June 1, 1945 and as luck would have it, ran into more severe weather as they rounded the outer banks of North Carolina. As a result, even more leaking was taking place because of the abusive conditions. But, for the most part the welds were holding and the ship continued oncourse for New Orleans.

On June 9, 1945 the ships entered the mouth of the Mississippi River. Following a short stop at Little Rock, Louisiana to offload all of the remaining ammunition, they continued under the drawbridge and finally into New Orleans Harbor. Done and done!

In the weeks following their return to New Orleans, the LST-325 had all of its guns and armaments removed as well as any remaining fuel. It was towed to dry dock for a thorough inspection, and then returned to the Pendleton Shipyard where work began in earnest repairing all of the damage that nearly resulted in its untimely death in their North Atlantic crossing. The work continued through June and into July.

It was just July 7, 1945, when Clifford E. Mosier, now a Lieutenant Commander was formally replaced by Lieutenant Robert Chitrin. This was clearly a surprise to all considering the quickness of the move especially in view of the incredible successes captain Mosier had managed to accomplish in his two and a half short years as the skipper. Some years later he reflected when he wrote, “I have often regretted my failure in not obtaining all your names and addresses but my departure from the ship in New Orleans happened very fast. About the second day after arrival there, My Exec informed me that an officer from the base was waiting to see me. The moment I saw him, I knew he was a psychiatrist. They always have a sneaky look. He asked me just one question, “Do you sleep well at night?” My answer, mixed with a few choice cuss words, convinced him otherwise. I think he may have also interviewed some members of the crew and some one told him, “The old man is driving us crazy.” Anyway, I shortly got orders which clearly stated “IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST,” transferring me to a new and larger LST being outfitted in Baltimore, MD.”…”I have often said and I will repeat it here. I know I had the best crew and the cleanest ship of any LST in the Navy. I was proud of you then and I still am.”

Clearly the crew was saddened by this turn of events when they were now missing the one man most responsible for their safety and their very lives. Throughout their time together they dodged submarines, bombs, strafing and guided missiles as they at times fearfully remained steadfast and faithfully completed their tasks and their part in ending the war. This feeling was best reflected by the words of Motor Machinist Mate Chet Conway when he wrote, “I reported to the Main, and I do mean the “Main Man” and Captain Mosier. None finer in the U.S. Navy. There aren’t enough words in the English dictionary to describe this man. One helluva officer, honest, loyal and smart. If it wasn’t for Captain Mosier, I don’t think the boys on the LST-325 would be around today, at least most of them.”

Many of the crewmembers were rotating through much deserved leave schedules during the repair period through most of June and into mid-July. However, most of them had returned to the ship by July 18th and resumed their duties. For John Roberts’ part, he returned home to the love of his life, Marian Noreen Flinn and married her in Faribault, Minnesota on June 23, 1945. He then brought her back with him to New Orleans until he ended his enlistment on September 12, 1945. John remembered this time when he later wrote, “I was in the first half to get leave in New Orleans. I went home on thirty days leave and got married. I brought the wife down and stayed until it was over, August 1945. I was discharged in New Orleans in September. I went back to work at the same electrical shop I had been with before. Spent over thirty years there as part owner for part of that time. My wife and I had four children one boy and three girls. Nine grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.”

John had served onboard the LST-325 from February 1, 1943 to September 12, 1945 when his enlistment ended. He reported aboard as an E4 Third Class Petty Officer Electricians Mate and advanced through the ranks during that two and a half years to his honorable discharge as an E7 Chief Petty Officer Electricians Mate. He was always fiercely proud of his time in the Navy and grew immeasurably from his experiences with the crew of the LST-325.

John himself put it best when he recalled, “How can I name any of them best friends, there were all of us! We all thought the world of each other, regardless of any personalities that could have come into play. We were shipmates! Getting back to best friends, I will start with the best…Jim Bronson, Jack Greenly, Bill Hanley, Mosby, Conway, Ninness, Mehan, Tierney, Brown, Dessinger, Kolar…the whole crew. I can’t list them all! If I were to choose a place, or a group of guys to go anywhere with I could never have chosen better. I’m so glad for the experience and I feel sure all of my buddies are too. I guess being in the service did change us. I can’t describe how. In many ways, I guess. We were not the same guys that left, I’m sure. How could we be after two or more years on that great ship. I hope it’s brought back for all to see. It’s the best ship! LST-325!”

The LST-325 was decommissioned on July 2, 1946 after nearly three and a half years of active and honorable duty. She was however brought back into service in 1963 and transferred to the country of Greece as part of a grant from the U.S. Military Assistance Program. There it was redesignated as L-144 Syros and served a country once again until it was decommissioned in December of 1999. John Roberts did however eventually get his wish when in 2001 after extensive efforts on the part of the United States LST Association she was brought back to the U.S. and is now fully restored and operational. It is home ported in Evansville, Indiana as the primary part of The USS LST Ship Memorial, Inc. With great joy in his heart, John did indeed have the opportunity to visit his ship once again while in his 90s in the company of his son John G. Roberts IV. John G. Roberts III passed away on March 26, 2016 at the age of 95. A life well lived.

Comments